Hip Dominant vs. "Knee Dominant"?

I recently had a discussion with a few folks online regarding how to differentiate between a “Hip Dominant” exercise and a “Knee Dominant” or “Quad Dominant” exercise. One person had read an article by Mike Robertson in which he offered the following formula:

Angled Torso + Vertical Tibia = Hip Dominant (Hip Hinging Patterns such as deadlifts and kettlebell swings)

Vertical Torso + Angled Tibia = Quad Dominant (Squatting Patterns such as...squats)

Angled Torso + Vertical Tibia

Another definition comes from the incomparable Dan John:

Maximal Hip Movement + Minimal Knee Movement = Hinge (Hip Dominant)

Maximal Hip Movement + Deep Knee Movement = Squat (Quad Dominant)

Maximal Hip Movement + Deep Hip Movement

Of the two, John’s is the easiest to understand and has the most utility. Robertson’s has a weakness in that split squats and lunges tend to have a vertical tibia and a vertical torso (the origin of the discussion), which either requires another category:

Vertical Torso + Vertical Tibia = Lunge Variation,

or just has you toss lunge variations in with the Quad dominant exercises. John’s does that, placing lunges with the squats, but the difference with his model is that the exercise grouping does not clearly run counter the proposed definition. It isn’t exact however, and so we could give Dan’s groups an additional category as well:

Moderate Hip Movement + Moderate Knee Movement = Split Squat or Lunge Variation

Moderate in this case might be around 90 degrees of flexion, whereas “Deep” or “Maximal” would be around 120 degrees of flexion.

About 90 degrees each of hip and knee flexion

It might make sense to look at these exercise groups as three different groups, rather than just two, for a few different reasons. First, they correspond most closely to different athletic functions (with a great deal of crossover to be sure. After all, we’re still talking about lower extremity extension against load):

Squatting: jumping from a standstill, as in rebounding under the basket or blocking in volleyball

The ladies on the right will jump straight up. So did the setter.

Deadlifting: forward sprinting, or jumping from a double leg plant after an approach like spiking a volleyball with a four-step technique.

This lady on the right will jump with an angled torso and a hip hinge.

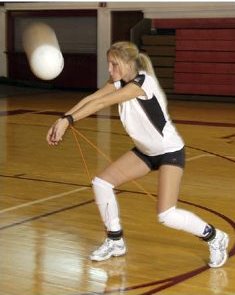

Lunging: Deceleration in the case of a forward lunge, or acceleration in the case of a reverse lunge, at least as it applies to forward locomotion. Generally though deceleration takes place outside of the sagittal plane.

Gimmicky sports performance tubing included.

Another potential consideration: What occurs when a perturbation is applied to someone in static unsupported standing. For a non-elderly person, the lowest level of response is what is known as an ankle strategy, which corresponds to squatting (tibial movement causing flexion at the ankle and knee, with the trunk staying upright). As the force applied increases, they will switch to a hip strategy, leading to movement at the trunk, similar to deadlifting. Finally, if the force is great enough, they will step in the direction of the displacement of their center of mass to maintain their balance, as in a lunge.

Dude in the blue pants pushed her from behind with his force-field eyes.

There is a problem with the three-group model however. In the article by Robertson he hints at a point of real practical concern between the two divisions of dominance, when he makes his two exercise groups not ‘movement’-based, but ‘muscle’-based, grouping them by the amount of quadricep contribution. This makes sense, because the primary reason for placing these exercises into the two groups is to allow higher volumes of lower extremity training while still allowing recovery to take place. This is accomplished by alternating the prime movers between the anterior and posterior muscle groups. For example, performing a Front Squat on Day One to emphasize the quadriceps, and a Stiff-legged Deadlift on Day Two to emphasize the hamstrings and gluteals. If you add the third lunging group to a third day as postulated above however you end up with a program that places excessive focus on the quadriceps relative to the hip extensors and also does not allow for maximal recovery of the quadriceps.

What we’re really talking about when we talk about grouping lower extremity exercises is how to train them as frequently as is productive, without engendering excessive localized muscular fatigue. It follows therefore that although it is generally counterproductive to look at exercise selection in terms of isolated muscle groups rather than functional movements, the contribution of the quadriceps should be the determining factor in placing lower extremity exercises into groups. Also, since I'm spending my Independence Day on semantics, I wonder if 'dominant' is even the right word. I don’t know for sure, but I suspect that in the squat or single leg squat the glutes and hamstrings probably generate more force in aggregate than the quadriceps do.

Here’s an example of how it might shake out in practice, keeping in mind that we want to include all three functional patterns--hinge, squat, and lunge--without training the quadriceps on consecutive days:

Day One: Front Squat, Goblet Squat, Trap Bar Deadlift or Single Leg Squat

Day Two: Deadlift, Stiff legged Deadlift, Single Leg Deadlift orKettlebell Swing

Day Three: Lunge or Reverse Lunge, Rear-Foot Elevated Split Squat or Step Up

Day Four: Deadlift, Stiff legged Deadlift, Single Leg Deadlift or Kettlebell Swing

One other thing: though we do not want to overcomplicate things by introducing a lot of exercises that need to be taught to your clients and patients, it will be necessary to substitute exercises at times for variety or because of practical considerations such as pain, injury or equipment availability. In this case keep in mind that it isn’t always ‘this-or-this’, it’s a continuum. Below is a vastly abridged example, with exercises ranked from lesser to greater quadricep involvement:

Straight Leg Deadlift

Deadlift

Slideboard

Split Squat

Step-Up

Back Squat

Rear Foot Elevated Split Squat

Front Squat

This list isn’t backed up by EMG evidence, and the sequence, even if it’s AlmostMaybeSomewhat correct, won’t hold true for everyone due to individual structural anatomy, balance of strength between muscle groups, and firing patterns. I just included it to illustrate the fact that although it’s critical to simplify things, you also want to avoid designing your program with a Slideboard Split Squat on Day One and a Back Squat on Day Two.

The ULTIMATE in Quad Dominant exercise (not recommended). Note also the seatbelt and the use of fancy words to make the thing that every single selectorized leg extension machine ever did sound scientific-like.