The Cat With Ten Lives: Abdominal Hollowing

There’s a saying about fads in certain circles in the performance industry about a pendulum swinging too far in one direction, then as a result of early over-enthusiasm and failure of the trend to end poverty and war, swinging too far back in the other direction. One of the big trends seen in the 20 years or so that I have been paying attention to this stuff is the use of the abdominal hollowing maneuver. The trend started with a fine book by Australian researchers, Carolyn Richardson and Paul Hodges, who found the following:

a consistent activation of a deep abdominal muscle (the Transverse Abdominus/TrA) in response to both reactive and volitional movements of the trunk and limb

a consistent (though varying in intensity) activation of the TrA regardless of direction of motion: I push you forward, your back muscles engage, I push you backwards, your abdominal muscles engage. But, the TrA engages no matter what direction your trunk, or limbs are moving, or resisting movement.

a general delay in activation of the TrA in people with lower back pain.

I was fortunate to come across this information in the late 90’s while working at Mike Boyle Strength and Conditioning (way back when it was Sports Acceleration North). I was yet to start PT school and was somewhere in the 5-6th year of back pain that was (retrospectively) not the worst ever, but was essentially constant and sufficient to keep me from participating fully in sports and from being in a good mood generally. I had been to physical therapy, had an epidural injection, and was toying with accepting the suggestion of surgery from my MD when I started working for Mike. I remember very clearly the program for athletes with back pain on the wall:

Angry Cat (with draw-in)

Elbow Bridge (plank-type motion with the elbows on ball)

Pushup Bridge (hands on ground, feet on ball)

Back Bridge (feet on ground, back on ball)

This was the late 90’s, so of course everything had to be done on a ball.

Admittedly, In my early 20's I had a different analysis of the cost-benefit ratios of stuff like this.

I attacked the draw-in with all these exercises vigorously. About three months after starting Coach Boyle approached me and asked how my back was, and I remember being a bit dumbfounded as I found myself telling him that it was feeling much better (ever notice how when we’ve been in pain we’re surprised when our bodies are performing their normal functions silently?). At that point everything clicked--so I thought--and was sold on the TrA. Once I got out into the clinical world, all my back patients were doing angry cats with a draw-in.

This quickly spread into the general fitness world, perhaps too quickly and certainly with a much broader application than appropriate. This coincided with the rising popularity of Pilates, which focused heavily on a drawing in of the belly with most exercises, but it was seen in weight training as well. Trainers and magazine authors were advising clients to draw-in when squatting or deadlifting (why is this wrong? Briefly, because the drawing in alters the angles of pull of the other trunk muscles, negatively affecting their ability to stabilize the spine). There was information in the Hodges and Richardson book about other deep stabilizing muscles, including the pelvic floor and the diaphragm, but for some reason their contributions were ignored in favor of the TrA and to a lesser extent, the multifidus. The draw-in was what hit the Tipping Point, probably because the draw-in was associated with ‘work’ in a way that breathing or holding in your pee is not.

Malcom Gladwell wouldn't return my calls about plugging his book here, so you get this.

Over time more and more good literature has arisen causing me to alter my treatment strategies and move away from the draw-in as an exercise, but I have always remembered how adding the maneuver to my programs made such a positive difference in my life and how it seemed to work--albeit as a component of a larger program--for many of my patients. I do think there are two reasons to sometimes include it in the interventions for some patients with lower back pain.

One is the theory that it is difficult to fully engage a muscle in function that you can’t engage in isolation. I believe that Mark Verstegen at Exos subscribes somewhat to this theory with the 'Isolate to Innervate to Integrate' process. Shirley Sahrmann PT, PhD does as well. There is some disagreement here however: I heard her elucidate this point as a rebuttal to Gray Cook during a joint interview. In my practice, the answer is in the middle somewhere (commitment issues?). Isolation might help for some folks some of the time but not for others.

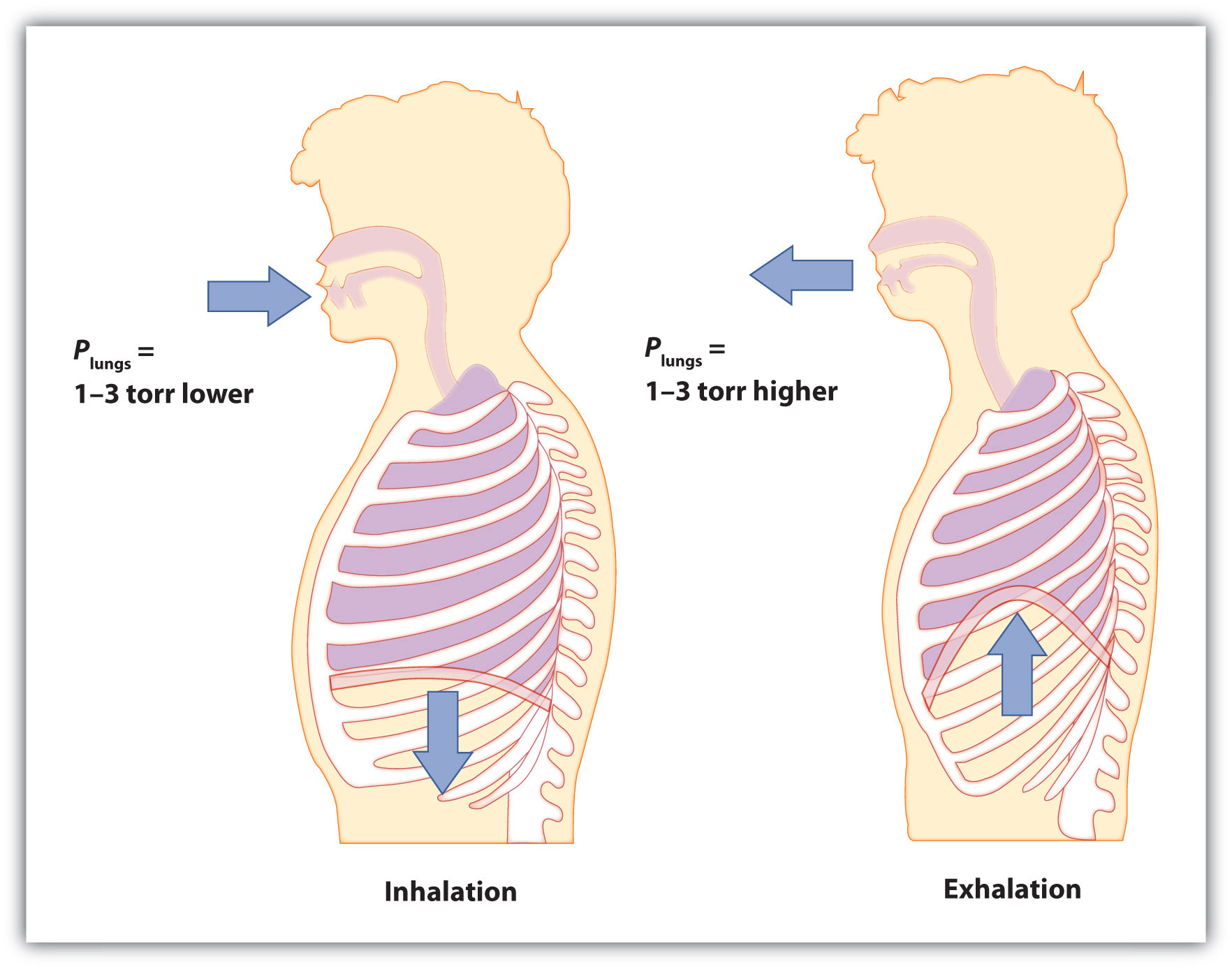

Two, which I think is much more likely, involves the way the Draw-In is taught, at least by me. Typically when you first ask someone to draw-in, they simply inhale deeply through their mouth and puff their chest out. This type of breathing is less than optimal for a myriad of reasons and also creates a false sense of hollowing due to the change in the spatial relationship between the chest and the stomach. To counteract this, I always taught diaphragmatic breathing first: breathing in through the nose to allow the stomach, then the ribs, to expand outward as the abdominal viscera compresses and the lungs fill with air. Once they could do this, I would ask them to add the draw-in to their exhalation, hold the exhaled position for 2 seconds, then inhale as they relaxed the draw-in. Though it’s impossible for me to say with certainty, I now believe that a huge part of my success with this maneuver is that as we performed it, it was inseparable from diaphragmatic breathing.

Nice Zone of Apposition. It looks like a ski slope (I included this picture for all of the PRI people out there)

In terms of application, I would offer the following suggestions:

The draw-in should generally be performed as an isolated exercise, preferably against gravity in the quadruped or prone position, and never in situations of axial loading.

It should be coordinated with the exhalation during diaphragmatic (rather than apical/chest) breathing

Once people can do this movement consistently without cues, alterations in respiration, or compensation, they probably don’t need to do it anymore and continuation will yield limited returns.

- To train trunk motor control/stabilization (including the TrA) in a functional manner, simply maintain good, tall upright posture while maintaining diaphgramatic breathing, then add limb movement to vary the demands on postural motor control.