Applying Lessons from Endurance Sports to Field Sports

Coach Magness

Steve Magness, author of The Science of Running and former sport scientist at the Nike Oregon Project and current cross-country coach at the University of Houston was the first lecturer at the Seattle Sounder's SSW and had some interesting points regarding the applications of certain aspects of distance training to field sports:

First, what is the definition of Endurance? There are a lot, and most have lots of caveats and conditions and still fail to provide a complete picture. His brilliant take: Endurance = Extension. Operating from this definition, not only do we eliminate discussions of different energy or body systems, or argue that football players do or don’t need endurance, or whatever. Endurance is the ability to keep performing, like you’re performing. Done.

100 miles? Extension.

49 Reps with 225? Also extension.

World class cross-country runners taper much less than the science suggests that they do. Steve implied that this shows that the science is not correct. Maybe it is, maybe it isn’t, but there are a lot of world class athletes (probably less in the olympic sports) that succeed in spite of certain aspects of their training. Would need a pretty large sample size to test this in a meaningful way, and a lot of creativity to reduce any placebo effects.

Steve told a story (the details here are going to be lacking, but you’ll get the idea) of a 3 and 5K runner who performed very well at a competition in the 800m. Coach Magness decided to make the 800m this athlete’s race, trained him like an 800m runner and the guy was terrible. Then he decided to have the athlete return to training with the 3/5K athletes and sprinkle in a bit of speed work. This got the athlete to perform. Obviously there is a big deviation from the principle of specificity here, and I wanted to know how he determined when and how to make this deviation. His suggestion was to find areas of good performance (ie, for what distance is someone putting up good numbers against the averages of other high-level athletes) that also have relatively low Rates of Perceived Exertion for that particular athlete.

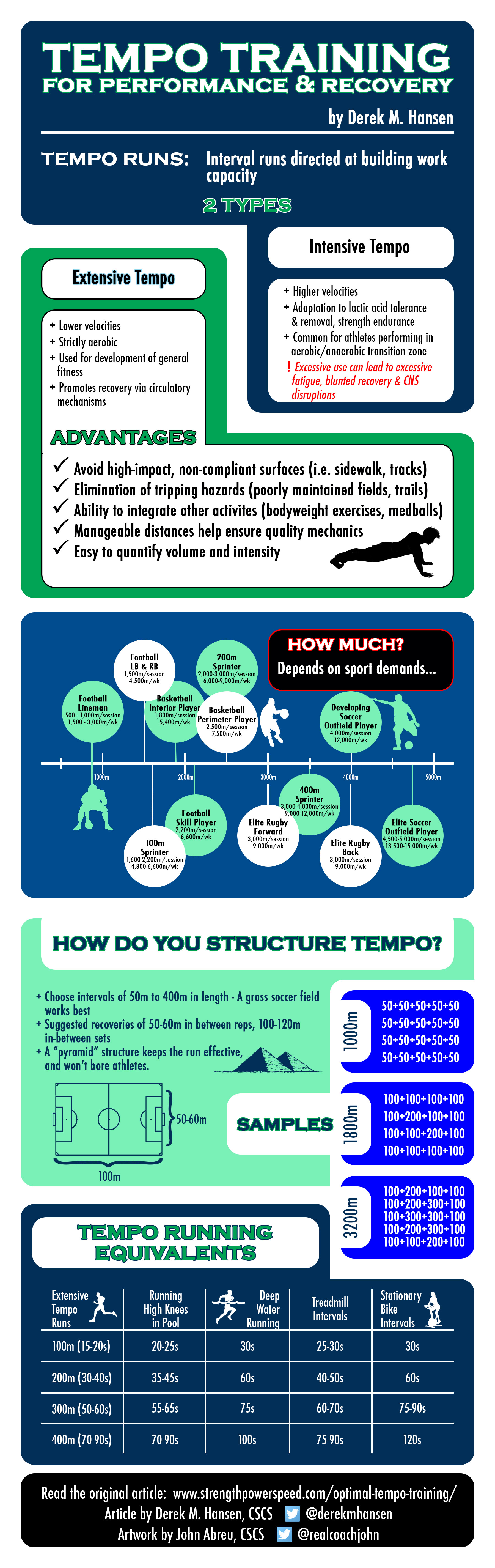

Using Tempo Runs as an injury-prevention method for hamstrings: Somewhere, there is apparently an article by David Joyce about this, though it hasn't been in my capabilities to find. It has been found that 80% of max sprint speed equates to the position of greatest hamstring stretch; Steve, among other presenters, felt this to be prophylactic against muscle strain. I should note (as Vern Gambetta did, vigorously :) that addressing the hamstring is only one component of preventing hamstring injury.

The utility of encouraging changes in stride frequency and length for the purpose of entraining movement variability. There’s a simple way to do this: using metronomes (maybe music of different tempos also?). There’s a simpler way: running next to people with different stride frequencies.

His recommendation on the amount of speed and/or plyometric work the day before the game to enhance neurological readiness: about 120 meters total, or about 8-10% of normal training volume.

Monotony can be a stressor. Doing the same workout over and over again can result in an increase in RPE despite an unchanging workload. A possible answer to this is dislocating the athletes’ expectations: avoid letting them know what the workout will include or when it will be over. An obvious example is holding the number of (planned) shuttle/tempo run reps close to the chest. This can reset a ‘false’ increase in RPE due to the monotony of knowing what is coming next. I would add however that not knowing what is coming down the pipe can be a stressor as well. Tom Brands tells the story of when he was a wrestler at Iowa and Dan Gable was running a practice that finished with live wrestling drills, over and over and over. He kept saying ‘this is the last one of these’, but there would always be more torture coming. Finally one wrestler, pushed past his limit, cracked, began to cry, and started screaming up at him: “you’re a liar, you’re not a good person, a man of your word!” Gable threw apples at him.

Dan Gable and Tom Brands.

The last story is a good segue into the final point: mental toughness. There was a lot of discussion about this, a good deal of it concerning coaches, particularly football coaches of the old school, designing conditioning programs as a method to create ‘mental toughness’. There are lots of problems with this approach, including loss of specificity with training, having athletes come to regard conditioning as punishment, and physically driving the athletes into the ground. Additionally, there is the point I touched on in the article on Activity Vs. Achievement, which is the danger of seeing extremes of effort the end goal rather than the means to obtaining it. Coach Magness doesn’t talk with his athletes about mental toughness. Rather, the goal is self-control. Can you consciously override the signals from your body telling you to slow-down or quit? Can you stay relaxed, focusing on technique and strategy in the face of the fatigue or adversity? Training with this mindset is an advantage because the focus is positively associated with the process (strategy) of winning, rather than simply blasting through obstacles to it.

And here, we end it, just as we began. A simple way at looking at a powerful concept.