The Importance of the Unimportant

I can’t tell you how many times I have had other clinicians tell me that they don’t test or train shoulder extension ROM. For years I didn’t do it myself. When taking goniometric measurements, bringing your arm straight back behind you just doesn’t have the cache of flexion to an overhead position or a 90/90 external rotation when explaining to an insurance case manager why someone deserves a PT visit or two. Additionally, when we reach behind us, we’re usually performing a movement like horizontal abduction (to reach into the back seat) or internal rotation (to scratch our backs, or for the ladies to clip their bra). So extension ends up being the ignored movement when it comes to single plane motions. Then about a year ago I noticed that I seemed to have a significant limitation in the Apley’s scratch test. I self-tested the shoulder mobility test in the Functional Movement Screen.

Um...yeah. I can't do this.

Or this.

Bilateral 1’s (that’s not good for those of you not familiar with the FMS) due primarily to limitations in the lower arm, but my mobility was so poor that I was still able to have a drastic asymmetry right to left despite the ‘good arm’ not being mobile at all. This isn’t abnormal among either athletes or the general population, but it’s unhealthy and will lead to sub-optimal movement, which increases the risk of pain and injury. It wasn’t a motor control issue, at least entirely, so I set to work on increasing my shoulder internal rotation and thoracic mobility. I experienced fair results, but not as quickly as I wanted, so I started thinking a little bit more closely about what is actually happening when you reach behind your back. If we’re just looking at the glenohumeral joint itself (remember that there are three other joints in the shoulder complex) it is internal rotation primarily, but also shoulder abduction and extension. I tried a stretch that I had consigned to the dustbin while still in graduate school, and found that it was extremely restricted.

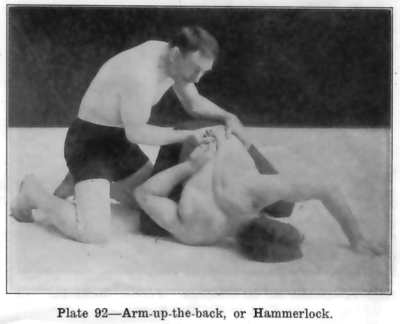

Everything old is new again.

I spent some time with it, and Immediately after performing this stretch, my shoulder felt much better and more mobile, and it showed in my Apley’s scratch test. Since then I have included it in all of my workouts, and then followed it up with active assistive ROM, using other muscles to assist it into an increased range, and then active strengthening into the new range to ‘lock it in’.

Using the posterior chain of the lower extremities to assist shoulder extension.

One interesting point is that the improvement was far greater than one would expect considering the apparently limited contribution of sagittal extension to an Apley’s. I’m not sure if I can explain this, though it could be from improved neurological relaxation, tissue stretching, mobilization of more proximal shoulder articulations such as the ST, AC and SC joints, or even a beneficial activation/inhibition of polyarticular chains such as those proposed by the Ron Hruska at the Postural Restoration Institute. I certainly have had improvements in my patients' IR (albeit transiently) simply by addressing breathing and rib mobility. Las April Connor Ryan, DPT at Drive 495 in New York City, even improved my shoulder IR (also transiently) by having me bite gently on a stack of post-its, so I am not ready to rule anything out.

The take-away for me was that sometimes assessing and addressing movements that may not seem functional or of great import at a joint where you want to improve another quality has the potential to lead you down rewarding pathways.

Something to avoid, or partner-assisted stretching?