Knee Replacements (or Hip Replacements, or Back Surgery) and Movement

Me and the best mom anyone could have.

My mother recently had a bilateral knee replacement. Most orthopods these days advise folks to do each replacement separately, but since anesthesia is tough on mom, she went for the double. To start off, let me brag a little bit about how tough my mother is. First, I wanted her to let me pick a Doctor, come to Portland and have the surgery done here. What better place to rehabilitate than in a house with two live-in PTs who love you, right?

Maybe not: the answer is your own home, in the city you live in.

They sawed off part of your leg bone and drilled into what remains. That's why your knee still hurts.

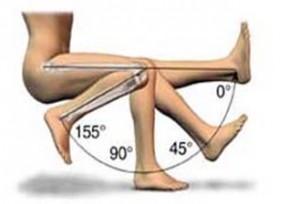

Most people are in the hospital for 3-4 days before transferring to a rehabilitation hospital after having a single knee done. Mom felt ready to go a day early, and left in two. And instead of going to rehab, she went home. To a two-story house. Without being hyperbolic, this is almost unheard of (no PT I know had heard of it). At first I was worried, but her hospital PTs and her home health PTs were both sending messages through my dad about how well she was doing, how good her range of motion was and how great she was walking. I figured out why when she mentioned it seemed like she was spending the whole day doing exercises. She was doing her exercises six times each day, and starting with heat and ending with ice. And then starting over again less than an hour later. I have worked with plenty of people that get paid to play sports (or paid to carry lumber for that matter) and I have NEVER met anyone who did their battery of post-operative exercises six times daily (rarely do I even ask that much of folks, though I have of a select few. Their shortcomings I’ll chalk up to my mom’s exceptionalism as opposed to my inability to motivate). The point of the story however is what happened later. I met mom ten days after her surgery in Reno to celebrate the life of my grandfather, and we did a few PT sessions that trip. What we went over though was not the exercises that she had been given by her hospital, home health, or outpatient therapists. Instead, we focused on moderately advanced balance, the way she walked, the way she moved. Without getting into the mechanics of what I saw, years of pain had altered the way she moved. I gave her a couple of simple exercises designed to begin addressing those issues that she could do at home and gave her ways she could increase the challenge once what I gave her became easy. She asked me why her therapists hadn’t addressed her movement, and the answer to that goes to heart of where we have opportunities to improve our medical care. I wasn’t having doubts about the clinicians treating her as she was at that moment; I knew that the most important objective for her would be to obtain as much motion in her knees as possible, followed by a recovery of the strength around those knees. But I also knew that the surgeon who performed the surgery, and the insurance company who would later decide whether or not to pay for the therapy cared about little beyond that. Once she had range of motion and strength that allowed relatively normal function, she was done. As long as her implant didn’t get an infection and in 3-12 months her knees hurt less, her surgery would be considered a success.

"Can you bend your knee? Can you straighten it? Yes? Good. We're all done here."

So with those as the goals, she was taught how to walk safely, but not how to walk properly. She had excellent exercises to strengthen the muscles that bent and straightened the knee, but little attention was paid to those that controlled the movement of the thigh and the shin (bottom of thigh and top of shin = knee joint). They were going to make the surgery a success, but without paying a lot of attention to either the potential causes of the underlying arthritis or the effects that the surgery might have on the rest of her body. This isn’t just applicable to knee surgeries. There is a reason why most lower back surgeries are not more successful than conservative treatments at reducing pain in the long run, and it is because many times we fail to address the root cause, which is often poor movement. We can expand it outward from the musculoskeletal system as well: why does the 40 year old with GI reflux, who doesn’t exercise, drinks a lot of coffee and alcohol and eats poorly end up with heart disease? Chances are that if we didn’t have pills that fixed the heartburn without fixing the causes there would be a lot fewer people with heart problems later on.

Here's a good goal for 4-6 months post-op.

We live in a world where we do have those pills however (and surgeries, and injections) and the fact that we are blessed to have these modern interventions is a good thing, not a bad one. But how should we balance the pound of cure with the ounce of prevention? On the clinical side, professionals like Physical Therapists, Chiropractors, Physicians, Athletic and Personal Trainers need to find ways to objectively assess quality of movement and then demonstrate with research how abnormalities can lead to other problems. Physical Therapists Shirley Sahrmann and Gray Cook, as well as Orthopedic Surgeon Ben Kibler are doing great work in this area. For the patients, always ask the cause. A colleague once told me, “we’re all on a march towards degeneration,” but there are reasons some people get painful arthritis in their 50’s and others in their 80’s; or why some people in their 20’s or 30’s get chronic lower back pain and others have a sore back for a few days every ten or so years. If you are seeing someone because of a musculoskeletal problem, ask them to tell you about how your posture, your habits, or your movement might be affecting your problem. “Walking normally like everybody else” was an important goal for my mother. Many of my patients have never expressed that desire to me, and I would like to think it’s because we begin talking about its importance before the pain that brought them in has been fixed.