Activity Vs. Achievement

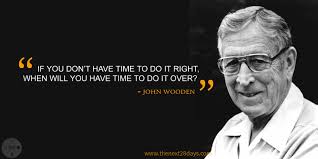

“Never mistake activity for achievement”

-John Wooden

Coach Wooden is popular these days. With the ever-expanding abundance of information on the subjects of skill, practice and creating habits--the science of getting good at something--it’s not surprising to see his name pop up. After all, the UCLA coach proved en route to 10 NCAA championships in 12 years (an .833 win percentage, not of games, but of national titles) that he knew how to earn success.

Much of his legend rightly centers on his character and the fashion in which he won, but also of great importance was his ability to maximize his teams’ practice time and get the absolute most out of every minute. He did his best to make sure his players were never just going through the motions; they were practicing the right things correctly. “Bustling bodies making noise can be deceptive” he said, as recounted in Doug Lemov’s “Practice Perfect”. What Wooden was after is what Daniel Coyle referred to as Deep Practice in his book “The Talent Code” (I told you there was an abundance of information). This article is not about skill acquisition however, though the above quotes apply. It’s about the gym.

I was re-reading a power point from a presentation by Thomas Plummer a few days ago and part of it was on the importance of selling strength training to new gym members:

The first thing you must do is to coach cardio. Every deconditioned person in the world thinks he or she is going to come to the gym, walk on the treadmill slowly for an hour watching television and that is all it takes.

If I stay HERE for 11 hours, I can eat THAT

TV Walking (or riding, or elliptical-ing) is the use about 80% of the cardio equipment in a commercial gym is put to. Another 15% are people gutting it out, straining, their heads bouncing like a bobble-head on Fan Day at Fenway Park. And just like unfocused basketball or musical practice, these methods of cardio aren’t very effective for whatever your goal is. Resistance training (vastly more suited to the goals of most people who exercise), is the same way. Just because activity is occurring does not mean that it is effective, whether your are working 'hard' or not. I remember how much emphasis was placed by my high school wrestling coach on arduous, demanding, grinding work in regards to conditioning and live wrestling. I am grateful for how well this message resonated with me, but in one important aspect I didn’t really get the big picture. I started wrestling as if hard work was the end rather than the means, and on some levels the idea in my head led me down paths that ran opposite to what would have made me better. In competition I might expend a lot of energy at inappropriate times to little effect in an effort to grind my opponent down, or in practice I might run through drills quickly to improve my conditioning or get as many (technically deficient) reps in as possible, rather than going slowly early on to master the finer details. One can get away with this to a certain extent in wrestling, which rewards explosive power, strength and intensity because it awards points for brief periods of control. I now compete in Jiu-Jitsu and submission grappling however, where dominant positions typically must be established for 3 seconds, and winning by submission requires mindful attention to the set-up. The details therefore become much more important. I also train for Thai Boxing, where like other striking arts it is necessary to stay relaxed in order to maintain good rhythm, reaction and timing. One of the biggest challenges in the sport is to remain relaxed while someone might be preparing to kick or elbow you, yet perfecting that mindfulness is a big part of what will allow you to avoid such a strike.

The greats frequently don’t look as though they are struggling. You won’t see a PGA golfer that makes it look hard to drive a ball 300 yards. There are thousands of distance runners that stumble across the finish line at a world-class marathon exhausted. Then there are the winners, serenely springing along, 24-25 miles into a race, fingers loose, jaws relaxed, perhaps even at a faster pace than at which they started. They are working hard, but you might not know it because of their efficiency. They are not choosing to show you how hard running 26 miles is, they are choosing to run correctly.

Look at how Deriba Merga suffers here. The guy looks miserable.

I would challenge you to take that idea to the gym with you, whether you like the exercise bike or kettlebells. Here are some tips:

First things first, turn off the TV. You are not training mindfully if you find yourself agreeing with Judge Judy’s smackdown of an ex-best friend that didn't pay their rent

- Be aware of your breathing. Coordinate it in some way, whether it is breathing in through your nose and out through your mouth; exhaling during the lift and inhaling while lowering; controlling the time spent in each phase of breathing; or simply making sure that you don’t hold your breath.

- Stay relaxed. It won’t always be possible everywhere (you don’t want your back to be too relaxed during a heavy squat) but energy used gritting your teeth and contorting your face isn’t energy going from your legs into the ground or from your bat to the baseball. It is a fact that certain feed-forward or ‘psych-up’ methods such as gripping a barbell as hard as possible will improve the ability to perform a heavy lift, but for sports that require speed, timing and precision in addition to force generation, this is not the most transferable method to use for the resistance lifts.